The rapid technological development and the growth of many niche markets into their own big markets (for example, Gong creating the Conversational Intelligence market) has left many buyers confused.

They're unsure about what makes one solution better than another, or, even worse, they're unsure about the value and benefits the product brings at all. Often, the positioning of a product makes or breaks its fit with the market.

I learned this lesson the hard way during my journey from digital marketing to product marketing, where a single statistic changed my perspective forever: a mere 1% improvement in brand positioning can drive a 2% increase in market share and boost customer loyalty by 5%.

This isn't just theory – it's a reality I've witnessed firsthand in B2B enterprise tech. My fascination with positioning led me to pursue opportunities to join a workshop with positioning expert April Dunford, whose framework transformed not only my approach to product marketing but also my entire career trajectory.

The experience taught me valuable lessons about implementing positioning strategies and navigating the real-world challenges that follow – from sales team resistance to market perception shifts.

In this article, I'll share insights from my decade-long journey across digital and product marketing, focusing on how modern positioning frameworks, particularly Dunford's methodology, can revolutionize how tech companies tell their product stories.

Through practical examples from my time at GWI and other enterprise environments, we'll explore the crucial distinction between positioning and messaging, and tackle the common challenges that every product marketer faces in the B2B tech landscape.

The origins of positioning

Let’s start by exploring the origins of positioning. The concept is attributed to Al Ries and Trout, who introduced it in their book published in 2001, so it’s over 20 years old now.

Their definition is that positioning is what you do to the mind of the prospect – it’s from their vantage point.

It’s less about the product itself and more about how you place that product in the prospect’s mind: the category, the associations you create. From my perspective, that’s a key truth about positioning.

The original framework for positioning

Now, let’s talk about the framework we use for positioning. I’m pretty sure most of you have seen this before. It’s the traditional positioning statement that goes something like:

Interestingly, this framework predates Ries and Trout – it comes from Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the Chasm, published in 1991.

I wish I could remember the year that the book came out and changed go-to-market strategies forever, but I don’t, I was 2 years old.

More recent examples of positioning frameworks

So, this framework – the positioning statement – is now 33 years old. Let’s look at the positioning statements and frameworks we have today.

Garner

Here’s one from Gartner, published less than 20 days ago. It’s essentially the same format:

The only difference is a small addition about “experience expectations,” but that’s all that’s changed in 33 years.

Miro

There are lots of versions out there, like this one from a Miro board that breaks things down slightly differently.

But from my perspective, they’re all the same – just different ways of filling in the gaps to create a positioning statement. Even with small improvements, it’s still fundamentally the same framework we’ve been using for decades.

MKT1

Recently, I came across an article from MKT1 that presents a similar structure but does a great job of simplifying things, especially when it comes to product type and comparison. It’s helpful if you're short on time and need to move quickly into messaging. I’d recommend this version if you’re working under time pressure.

Venture hack

I also want to give an honorable mention to Venture Hacks’ “high concept pitch” framework, where you compare your product to a well-known success story in a different field. For example, Instacart called their product “Uber for groceries.”

I hope no one reading this ever uses that – it can be problematic, often drawing unhelpful associations with market leaders that don’t benefit your product.

This framework is only helpful when you have less than five seconds for a pitch to somebody who does not know the domain in question or on the Dragon’s Den stage.

In summary, the problem with these frameworks is that they’re outdated. For B2B tech, they’re removed from today’s reality, where markets are far more competitive and saturated. It’s also hard to know how detailed or specific to get, as these frameworks don’t really guide you beyond simply filling in the blanks.

April Dunford’s positioning framework: How is it different?

That brings us to April Dunford’s framework. How is it different?

At first glance, it doesn’t look very different – you have your market category, target market, differentiators, and competitors.

But if you look closely, it works in reverse, starting with competitors rather than your product or target market. It’s also not just a fill-in-the-blanks exercise; it’s a series of steps you follow in sequence, and sticking to that sequence is critical.

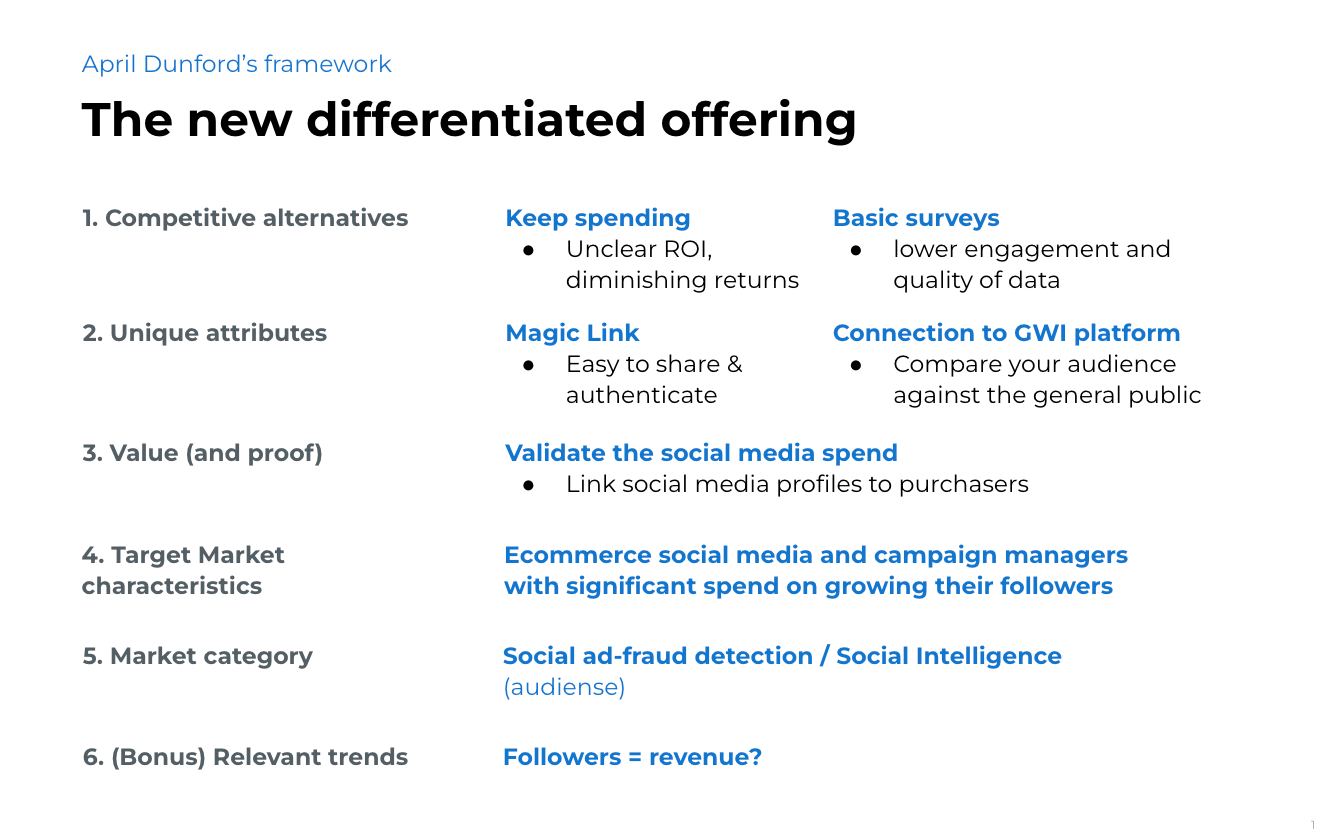

An example of bringing April’s framework to life

Let’s put this into practice with an example to bring it to life. GWI is a company I worked for years ago – it was one of my first product marketing roles. GWI is a survey data provider.

They buy access to audiences from panels and survey around half a million consumers every year across 46 geographies.

The survey is very detailed, lasting about two hours, and the data collected is stored on a platform.

Over time, it accumulates, so you can track trends. Brands can see things like who their buyers are, what newspapers they’re reading, what influencers they follow, and so on. It provides very granular insights into the audience.

GWI had acquired a startup called Pollpass. What Pollpass did was essentially a workaround to traditional panel providers. They had an app that anyone could sign up for. There are a lot of apps like this now, where you can earn small rewards or credits by answering questions.

For GWI, this was an alternative to panel providers, offering a faster way to gather data, and the quality of the data was presumably better because the app was conversational, rather than relying on long surveys.

The Pollpass team realized they had a new offering. They wanted to use GWI’s standard survey within the app, allowing brands to send it to their own audiences – not just the general public, but their specific buyers.

They also figured out how to leverage a new technology called a "magic link," which allows user authentication without passwords.

Instead of logging in, you click a button, receive an email with a link, and clicking that link gives you access. It’s a great solution – everyone hates passwords, so this was a nice improvement.

At the time, I was a new product marketer and was assigned to this project. So where did I start? With positioning. If I were to follow the traditional positioning statement, it might look like this:

Great, I’ve got the differentiators clear, and I’ve written the statement. Done, right? Unfortunately – or fortunately – by then, I had read April Dunford’s book, and I was fascinated. I was keen to try out her framework, so I didn’t stick to the traditional statement.

For some context, I was new at the company and had only done a soft launch before, which had flopped. There was no revenue – no opportunities came from the 20 contacts we had contacted. I was in a tough spot, and I felt the pressure to prove myself. I saw this as my chance. Putting April Dunford’s positioning framework into action.

I started by doing market research to better understand the space. Then, I brought the team together for a workshop.

Step one: Identify competitive alternatives

The first step is identifying competitive alternatives. This is about understanding what’s already available to customers before they come across your solution. It’s a crucial step and, in my opinion, what sets this framework apart.

It’s strongly connected to the "jobs to be done" concept: people don’t buy a hammer; they buy the ability to hang something on the wall. Your product is just one solution to their problem.

So, what problem does your product solve, and what alternatives do prospects currently use?

I refer to this as "killing PMs' darlings" because sometimes PMMs and PMs are caught up in their own world, thinking their new product is the only solution out there.

But if the problem is significant enough, there will most certainly be alternatives and workarounds, maybe more time-consuming ones, but likely cheaper too. And don’t forget that manual solutions – like using an Excel sheet or getting an intern to handle tasks – are always an option.

In Pollpass's case, the main competitor was traditional panel survey providers. But if we’re talking about sending a survey to a company’s own customer base, there are survey-building platforms like SurveyMonkey.

And guess what?

They even have hundreds of templates, so you don’t have to start from scratch. If a company needs something more specific or can’t find the right template, they can always hire freelancers to help craft a custom survey. So, we weren’t just competing with panel providers; we had to consider these other alternatives as well.

Step two: Zero in on differentiation

The next step is zeroing in on differentiation. What are the unique attributes that alternatives don’t have? This is essential because, in the B2B tech world, anything that isn’t a differentiator quickly becomes table stakes – there’s no point in talking about it. You need to focus on what sets your product apart.

For Pollpass, the differentiator was that custom survey providers didn’t allow surveys to be sent to a company’s own audience – this was something new. For survey-building platforms, we had the magic link feature as a key differentiator.

It was a great feature, but the question was whether it would remain a sustainable differentiator or if competitors would eventually catch up. Similarly, with freelancers, they could build surveys, but they didn’t have proprietary technology like we did.

You could probably find someone to build this for you if you’re really keen.

Step three: Value, value, value

Moving on to the next step: value. This is where you need to figure out the impact of those differentiations and the actual results you deliver thanks to them.

In the case of custom survey providers, it allows you to zero in on your audience, which is great, but you could absolutely do that on your own already. So, what is the value? Where is the real value?

Then, when competing with survey-building platforms, we have the magic link, but I have to ask – if you’re sending it to your own audience via email, why do you need to authenticate them? It’s all starting to crumble. The differentiators are collapsing; it’s not clear anymore.

Step four: Hone in on your target audience

We identified some gaps in the framework and went back and forth, but the breakthrough came when we focused on the target audience. This is another critical and impactful step.

I can't stress this enough: this is not just your ideal customer profile like "mid-sized companies in the UK and US." That’s not going to work. You need to zero in on the specific problem your customers have and get really tight on that.

Going back to Geoffrey Moore and Crossing the Chasm, there’s a strong link here to the concept of the "marquee client." - the client you release a press release with, showcasing the massive impact your product made.

As well as the first pragmatist clients who are compelled to buy because the problem is so big – they can’t wait. Zeroing in on this audience is the formula for crossing the chasm.

It’s the difference between a tactical product marketer, who’s just executing campaigns, and a strategic product marketer, who’s driving the go-to-market strategy. This is how you cross the chasm, prove the initial product-market fit, and create the case studies that will help you win the rest of the market.

The tighter your focus, the better. You can always expand over time. But initially, it’s about getting really specific. For example, in the case of Pollpass, we started with a marketer audience that we already had with GWI.

The new solution did not have the potential to open a drastically different target persona. So when do marketers have a problem sending surveys to their audience?

This was before product ads on social media – back when everyone was just growing their follower base. You could promote your page, but it wasn’t connected to a product yet.

So, there was this big debate about whether followers would actually translate into revenue. Meanwhile, social media was exploding, with more brands jumping in and putting big budgets behind it.

At that time, Facebook had just introduced "lookalike audience" targeting, which allowed brands to find demographically similar people to their followers.

It was a great opportunity for early adopters, but even more questionable return on investment – those newly bought followers didn’t necessarily know your brand or were able to purchase products (i.e. in countries where the product was not sold).

We had a niche audience with a real-world problem that suited Pollpass's new solution well. We refined the positioning to focus on social media and campaign managers, specifically in e-commerce, because they were the closest to trying to tie their social media spend to ROI.

We offered them insights into their social media audience using the magic link survey, which allowed us to authenticate buyers by email and compare actual buyers to newly acquired followers who hadn’t purchased yet. And subsequently to understand if the new followers they were buying had a good chance of converting to paying customers.

Another great thing happened with the Pollpass team. We realized the magic link differentiator wasn’t enough, so we explored how to further differentiate from other survey platforms, like SurveyMonkey.

They were open to integrating with the GWI platform, which allowed us to compare survey results. This added a lot of value because now you could compare your audience's responses with other market segments. That’s something you couldn’t do with a custom survey alone.

The difference in the positioning statements is huge. Through April Dunford’s framework, we honed in on targeting social media and campaign managers in e-commerce, focusing on those who need to calculate the ROI of their growing social media spend.

We enable them to authenticate their audience, validate their social media spend, and understand how to convert new followers by comparing them to data from the GWI platform. In contrast, the old positioning was too broad – targeting all marketers and researchers with a generic solution.

In the context of B2B tech, this difference is massive. My argument is that you need that tight, specific focus to get your product off the ground. Later, once you’ve grown out of your initial segment, you can expand.

The results of putting the framework into action

As for the results, I’d love to say we launched the product and created a new market, but a month later, the whole Pollpass team was shut down due to budget cuts. The project was gone, and I had nothing to show for my work aside from a positioning deck.

However, it had a huge impact on me. I got first-hand experience of how powerful product marketing can be – how it can change roadmaps and shape how a product is viewed.

I reached out to the product director from Pollpass recently, and he remembered our work well. He even said he became a fan of April Dunford. So, while it didn’t generate revenue, it left a lasting impact. At least on the two of us.

Final thoughts: “Why be so specific?”

To wrap up on positioning and messaging: you might ask, why be so specific? Founders will often push back because investors want to see big markets. But it’s critical to remember that positioning is not messaging.

Positioning is your battle strategy – how you’re going to win. Messaging is the weapon you use for specific channels and audiences.

Positioning will always get watered down when turned into messaging for a specific channel and audience, especially when there’s limited text space.

Look at Meta’s homepage: "Connection is evolving, and so are we." What does that mean? It’s so broad and vague, and it doesn’t communicate any differentiation.

On the other hand, I’ve seen some genius website headlines that focus on a key competitor, like how Coda was positioned against Google Sheets or Excel (as seen below). That’s specific, but not as specific as the positioning behind this messaging has to be to determine the go-to-market.

Love this @coda_hq billboard! #marketing #ooh #startups pic.twitter.com/pX0Swdu8Wy

— Kenny Mendes (@kmendes) February 21, 2020

That’s why positioning is so hard to unpick - there’s a big gap between the positioning and what gets executed as messaging.

But when done well, positioning can influence roadmaps, ensure product-market fit, and drive business growth by uncovering and solving real market problems – not just saying, "Hey, we’re different."

Stop just filling out the positioning statement. Put in the effort and the research to position products for real market growth.

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn

.svg?v=a8bbe6f9b2)