The human side of things is often lacking in the business world, but actually, research shows design-centric, AKA human-centered companies outperform the market by over 200%.

In this article, I’ll share seven human-centered design techniques that I’ve learned during my career that you can take back to your own organization.

There is the human side of everything that we do and in business these days, everybody wants to be data-driven, they want to see numbers and charts and as much data as possible from your systems and your tech.

There's also a lot of focus on best practices:

- What is everybody else doing?

- What's the gold standard?

In most companies that I've worked in, there's been the question: what are our competitors doing? Oh my gosh, we had this idea, and our competitor now just came out with it beforehand, we're behind.

Questions like these tend to get asked when trying to work out how you evolve your business, how you bring new ideas to market, and oftentimes that misses the human side of it, at the center of human-centered design and design thinking, which is so critical to customer experience.

Because after all, these are people that we're selling to, they're people that have jobs, they have their own needs and pains.

Human-centered design: a case study

I like to shape the narrative around human-centered design as different from innovation with a great case study about a group of students from the Stanford design school, also known as the D school.

These students - a cross-functional group, one MBA, some engineer, somebody in some other practice - all come together, go through this program called the D school to learn how to develop empathy for people and design new solutions for problems. That's the whole focus of the school.

They had a project where they were looking at Third World countries and this problem which is actually pretty significant. One out of 10 babies (or something like that) every year are born preterm; 15 million around the world and half of those are in India.

They're looking at this problem and the nature of the work they're trying to do is around what we can do to address this. One of the key things they learn as they're going through this, outside looking in, how can we address this problem, is that there's a shortage of incubators in the hospitals that are in the urban centers that serve a lot of people from the rural parts of Third World countries.

Short of incubators, oftentimes, they can be very costly relative to that society.

Question one:

Their first question or the first problem that they sought to address was this idea that maybe we can reduce the cost of this, and make it more affordable for those hospitals so there can be more, and more preterm infants can be served.

This sounds really great, to be able to reduce the cost of this really expensive thing is super innovative. That's a great example of innovation in that they've taken something that exists, and they are looking to improve it in some way through technology or whatnot.

But because they are part of this design thinking program, which is fundamentally different than something like just a simple innovation strategy, what they did is unique to this type of practice.

They left, they got out of the walls of their campus, and they went over to Nepal and India and they met with the people that were having these preterm babies; they lived in the villages and developed empathy for what they were going through.

In that experience, they discovered most of these people that are facing this challenge, these high death rates from preterm, can never even get to a hospital. They don't have means to travel, or a way to get to a hospital.

Therefore, the idea of having lower-cost incubators doesn't impact them at all.

Question two:

So they asked a different question - going back to the reduce the cost question, reframing this in a way that says, how can we create a baby warming device that helps parents in remote villages give dying infants a chance to survive?

When you look at the nature of this type of question versus the other more technical challenges product/feature-based question of a lower-cost incubator, they're fundamentally different in how you might approach creating a solution.

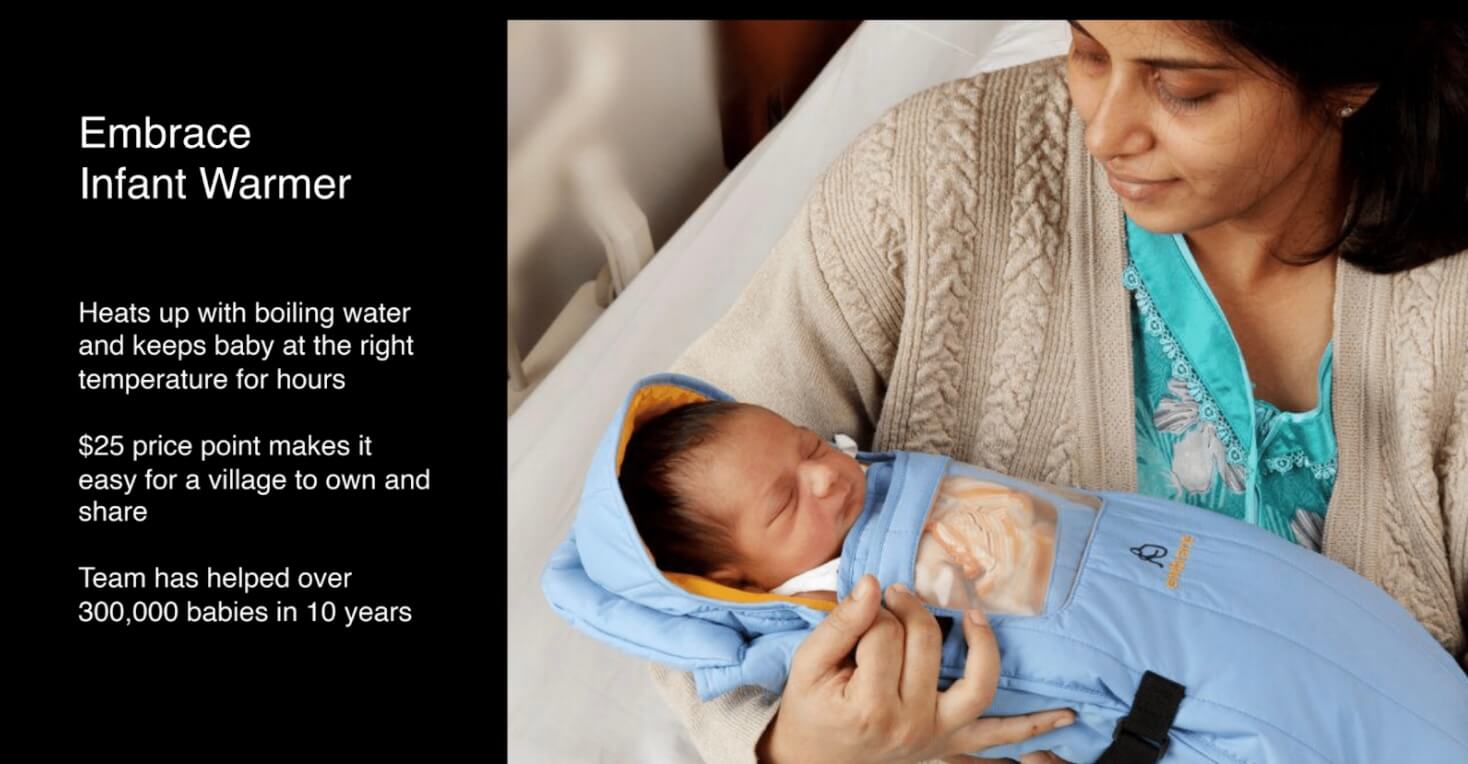

The Embrace Infant Warmer

The result of this was they ended up creating the Embrace Infant Warmer and after they finished their program, they've gone on to start this company.

Over the course of a decade or so, they have helped 300,000+ babies. The reason I like to tell this story is that this is actually what got me so interested in design thinking in the first place, and why I decided to pursue that as an area of practice and study, and bring it into the organizations that I work with.

The agenda

I'm going to share a few techniques with you in this article. There's not a big overarching agenda other than sharing some tips and techniques that I've found successful.

Before that, let's look at you should care about design thinking.

Design thinking, why should I care?

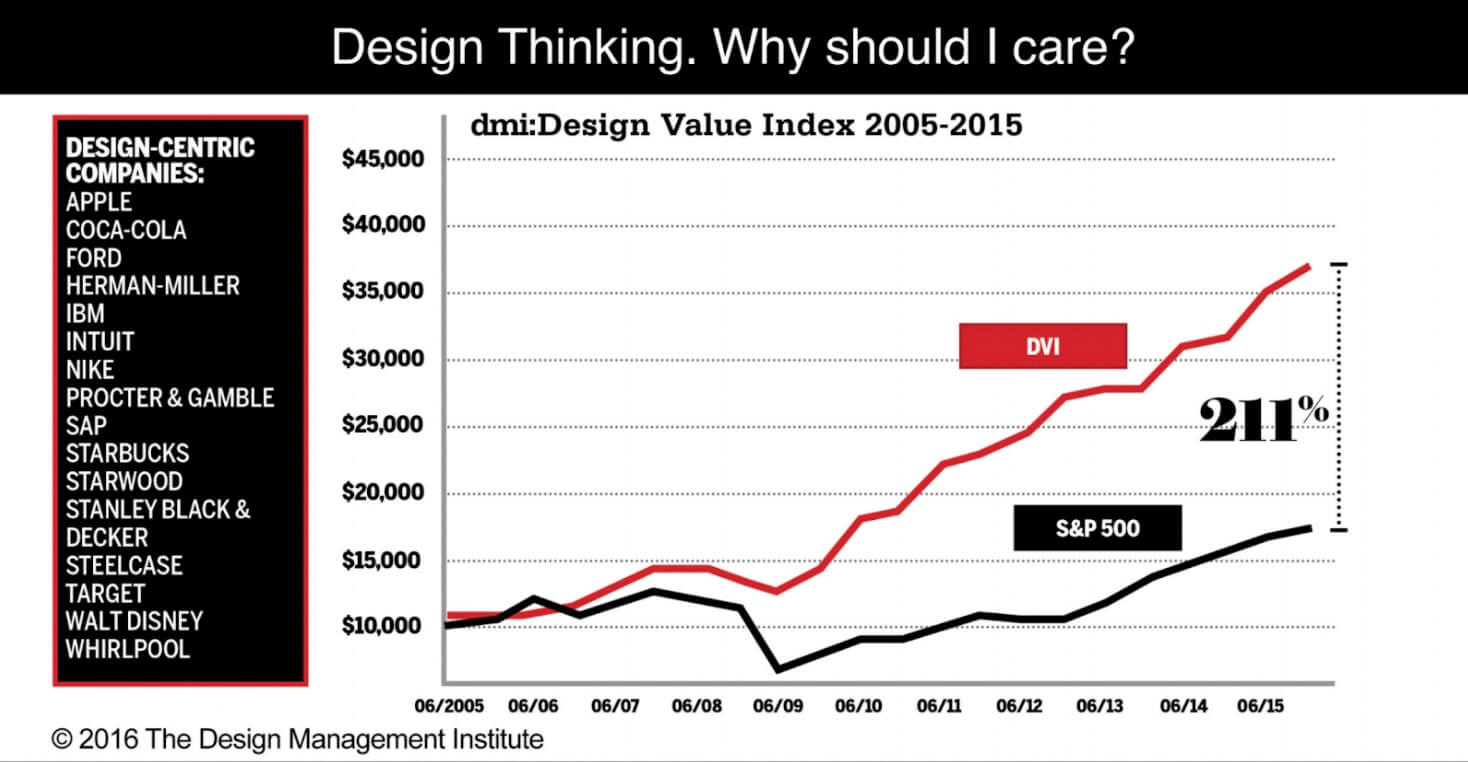

There's this institute called the Design Management Institute. They did a study and found design-centric companies outperform the market by over 200%. There you go.

Now, when you go to your management and say we should start doing human-centered design, that's how you show them.

There are a lot of different charts that illustrate what design thinking should look like, a lot of it starts with insights, ideation, develop prototypes, test, all that stuff. But what I like about this one, in particular, is it shows the messiness of it, because it's not a practice that's necessarily for the faint of heart when it comes to organization and checklists and clean processes, and stuff like that.

It's very messy, very collaborative, a very real-world tangible process that can be a lot of fun when you go through it. But this idea of the visual aspect of it appeals to me.

One of the things I tell people is if I could do all my work without a computer I totally would. Sticky notes, whiteboards, and all that stuff would totally be fine.

Technique #1: Ask a more beautiful question

You saw the difference in the two types of questions these students could have used to approach their solutions to problems.

The Goldilocks Principle

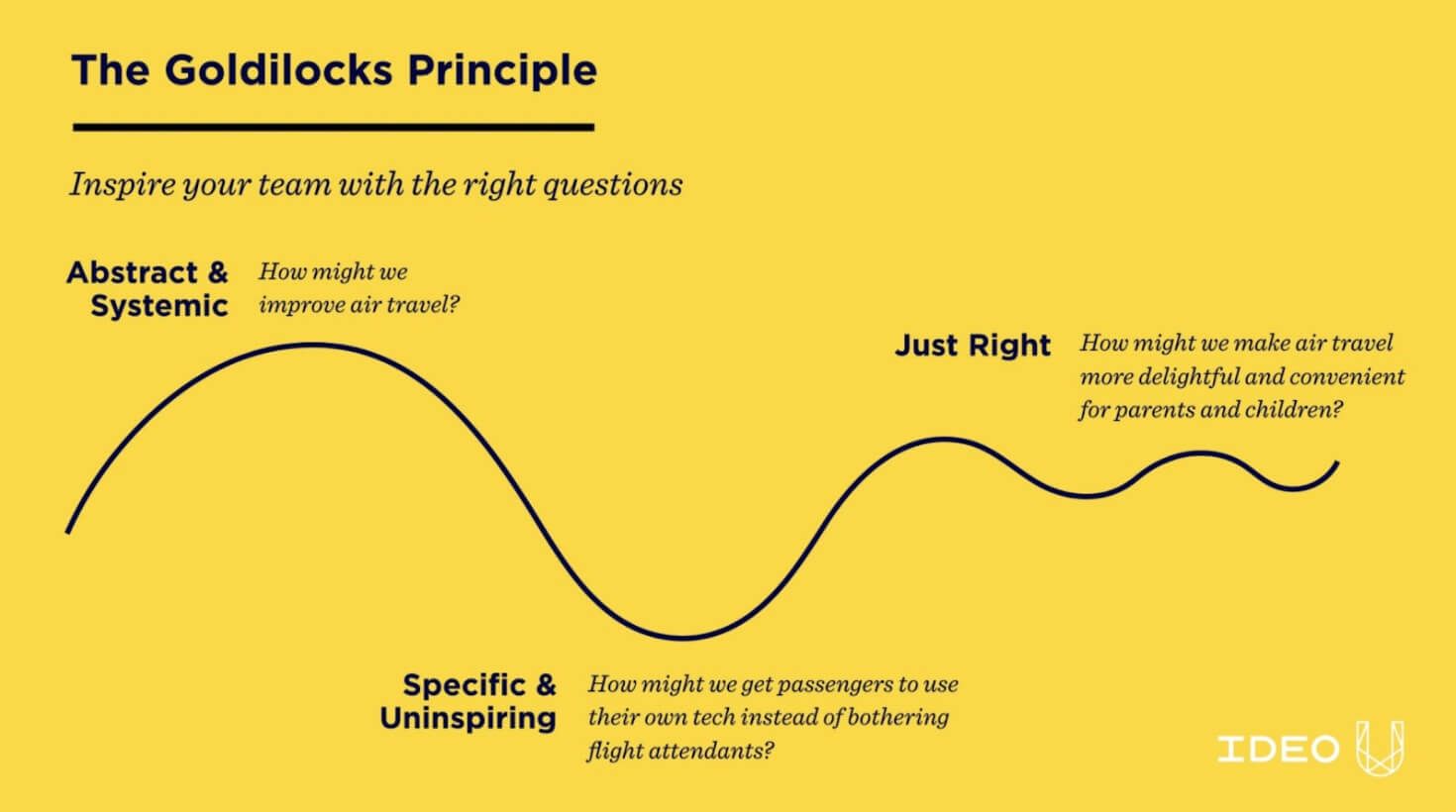

There's a spectrum of questions spanning too broad, too specific, and landing on just right - this comes from IDEO.

The abstract and systemic example above, how might we improve air travel? That's a big loaded question.

But then look at just right, how might we make air travel more delightful and convenient for parents and children?

It’s a little more specific. It puts the person in there, it's talking about the parents and children, it's talking about what incremental improvement we want to make about air travel but it's not too specific like the specific and uninspiring example at the bottom.

Applying engaging consumer experiences to the B2B buyer journey

A few years back - I was at Lenovo at the time working on a product that I had to take over - I attended a heavily B2C-focused marketing conference. It was amazing to see how innovative all these retail companies were being about their customer experience.

I came back to the team with this question: how might we apply these more engaging consumer experiences to the B2B buyers journey?

One of the main experiences that retail companies were exploring at that time was virtual reality. Based on that question, and several months of exploration, we ended up producing a virtual reality experience for a major trade show - I'm sure you all know about Gartner and CIO symposium - it was amazing.

It was like nothing else I'd seen before when it comes to an on-site experience interacting with customers. We had over 500 CIOs come through, on average spending 12-15 minutes with us, getting completely lost in this world that we had built around some of the different types of challenges they were trying to solve.

It was a cool experience but the main takeaway was it would have been a great idea for anybody to say, 'Hey, I've got a cool idea'. But the fact it started with the question of applying a B2C experience to the B2B buyers journey is where it all came from.

It wasn't about somebody having a great idea, there was more - there was a really good question to start with.

Find your co-conspirators

On that note of getting started in the space along with asking really good questions, design thinking, and going through this type of practice is not for everybody.

A lot of people will say, 'I just want to do things the way that I do them' or, processes aren't for them, 'I don't like new processes, frameworks, models and stuff like that'.

What I did at Lenovo in the face of that was create a community, which over time grew to be about 200 people. We would get together and apply some of these practices to each other's works, an ad hoc community because it wasn't top-down, there was no executive saying, "Hey, we're going to institute this as a practice so I brought it in and built this out".

I definitely encourage you, if you want to adopt something like design thinking, to find other like-minded people inside your organization that you can work with.

Technique #2: Interviews, active listening, contextual inquiry

I'm sure as a product marketer you do a lot of interviewing for personas and things like that but applying that same idea of the question to interviews, for example, I worked on a project for a couple of years, bringing a new product to market.

It all started with interviews with small businesses and I'd just sit there and ask the same question over and over, 'Tell me about the last time you bought a new digital tool'.

Problem theory: finding, buying, and owning business apps is hard

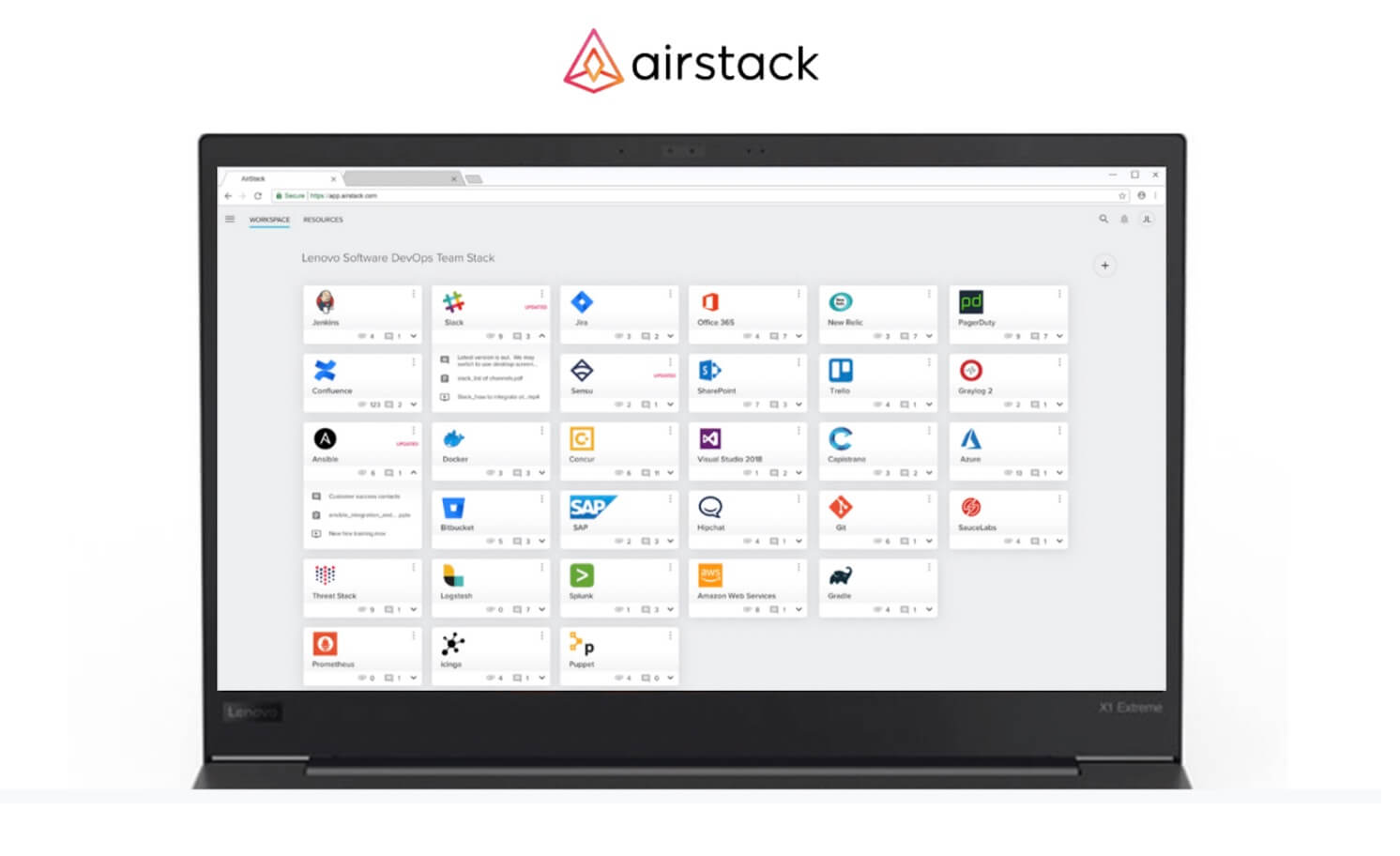

The stories I heard over and over from people about the pains and the challenges led to the development of a problem theory that basically finding, buying, and owning business apps is hard.

After hearing it over and over again, we really started to see this for ourselves too. There was a whole lifecycle of going through these things.

Where it really became interesting is applying another technique...

Technique #3: Outside worlds

Once you have this sort of problem theory or seed, the thing that's going to grow is what some call outside worlds.

Outside worlds is where you take this challenge, you take this problem, and you go explore it in different contexts or different settings.

In this case, I was at a conference, not for CIOs, not our target audience at all, and everybody was talking about this thing called Tech Stacks.

You've probably seen this type of chart, they were talking about using it as a way to communicate the business value they get from all these different tools they use.

This whole new nomenclature and people talking about how they'd solve this problem, which led to some exercises on site.

Technique #4: Prototyping

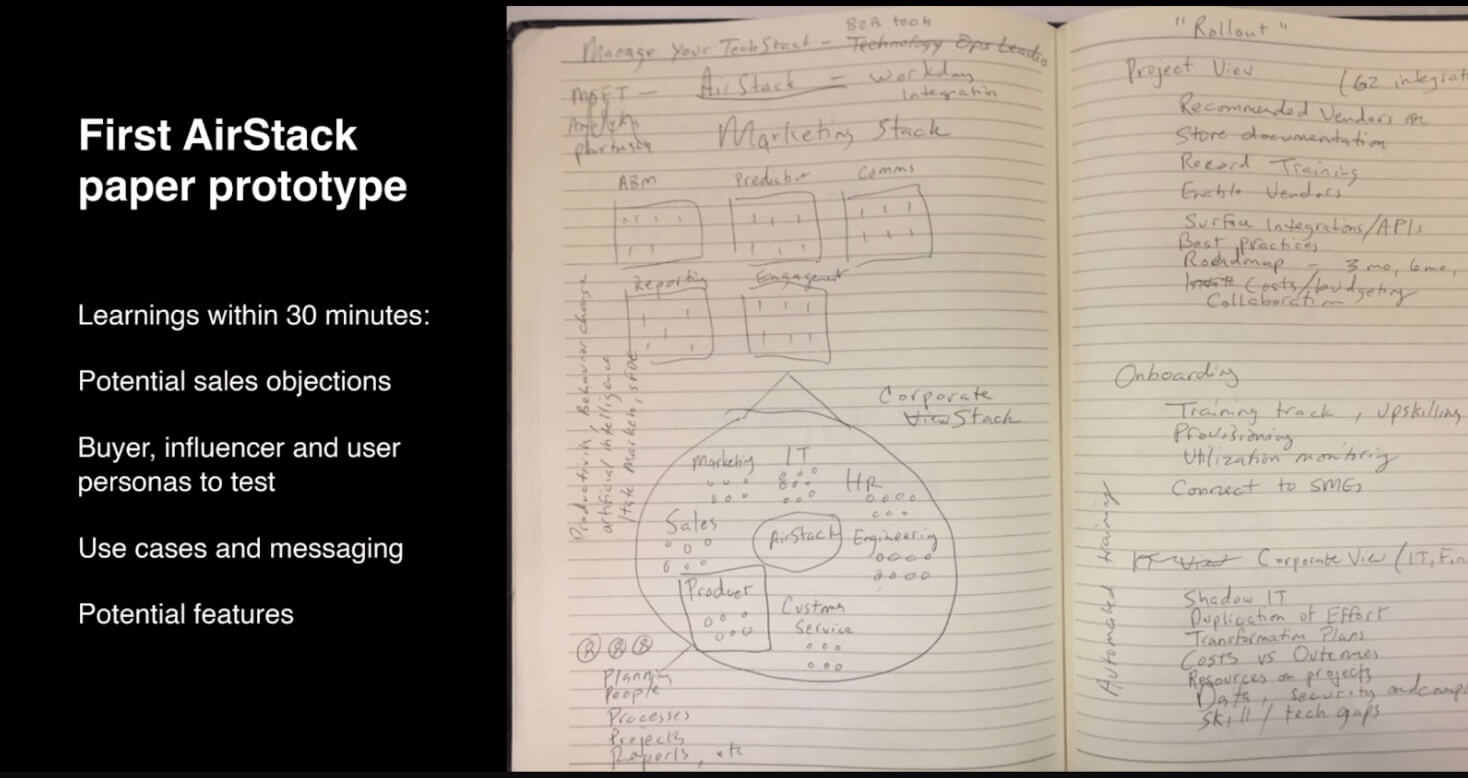

This was a paper prototype of a new product concept called AirStack, which was an evolution of a product that we were trying to breathe new life into, a more IT-facing product.

I sketched this out, it took maybe five minutes to get the idea down but the great thing about being on-site at that conference with all those people was I could get live feedback rapidly.

Within 30 minutes, what was just a small drawing had turned into different types of value propositions, sales objections, who might the stakeholders be, and what are different use cases for this concept.

Ultimately, that ended up coming to coming to life, there was a whole launch process around it as AirStack.

The gist of the story is it all started with the question of: what is it like for you to buy software?

The nature of the question was not to say we want to develop some new products but the nature of the question was, actually, we want to learn how to sell you software better.

What happened instead was that we created something that could help them solve that problem.

Hackathon style

On the notion of prototyping, there are a couple of recent events I've done that have been really fun, one with NC State that we called Moonshots where they wanted to reverse engineer the solutions to big meaty problems they're trying to address in the next 10 years.

In this case, bringing together cross-functional people to solve these types of issues with healthcare and things like that, can be a good setting for prototyping.

Rapid prototyping

Another organization I worked with, Walk West, spent months and months developing empathy for their potential buyers, and then went into a sort of design sprint - a 96-hour website redesign process.

So, when you're thinking about going from insights and empathy to prototyping, there are a couple of different flavors of ways you could go about it. There are a lot of resources on this but just so you know there are a lot of different options.

Technique #5: Think aloud testing

This technique is super fun because you realize that any product you have can be made with Post-It notes and a wall and paper.

You get people to try to do the job they're trying to do but while they're talking out loud about it, so you're able to hear exactly what's going on in their minds, and you're able to see how they would interact naturally with the world around them, if it wasn't for some product design that gets in their way.

Technique #6: Buy a feature

I was fortunate to have the Sugar CRM CMO as a participant when we were doing research on this.

This is a fun exercise that I adapted from another organization, buy a feature, where you take a lot of different value propositions, have a stack of paper printed out, and say you can place any of these pricing models on any of these value propositions.

It's not that you would price a product in this way but this interactive way to see how people think about the money and the value that they get from things brought a lot of insight back to our organization.

Our final pricing looked very different. But it's fun too, especially when the buyers are like, 'I really love this exercise, I'm want to do more of this’.

Technique #7: Walk a mile

The last one is the Walk a Mile technique. Everybody knows the adage of walking a mile in someone else's shoes.

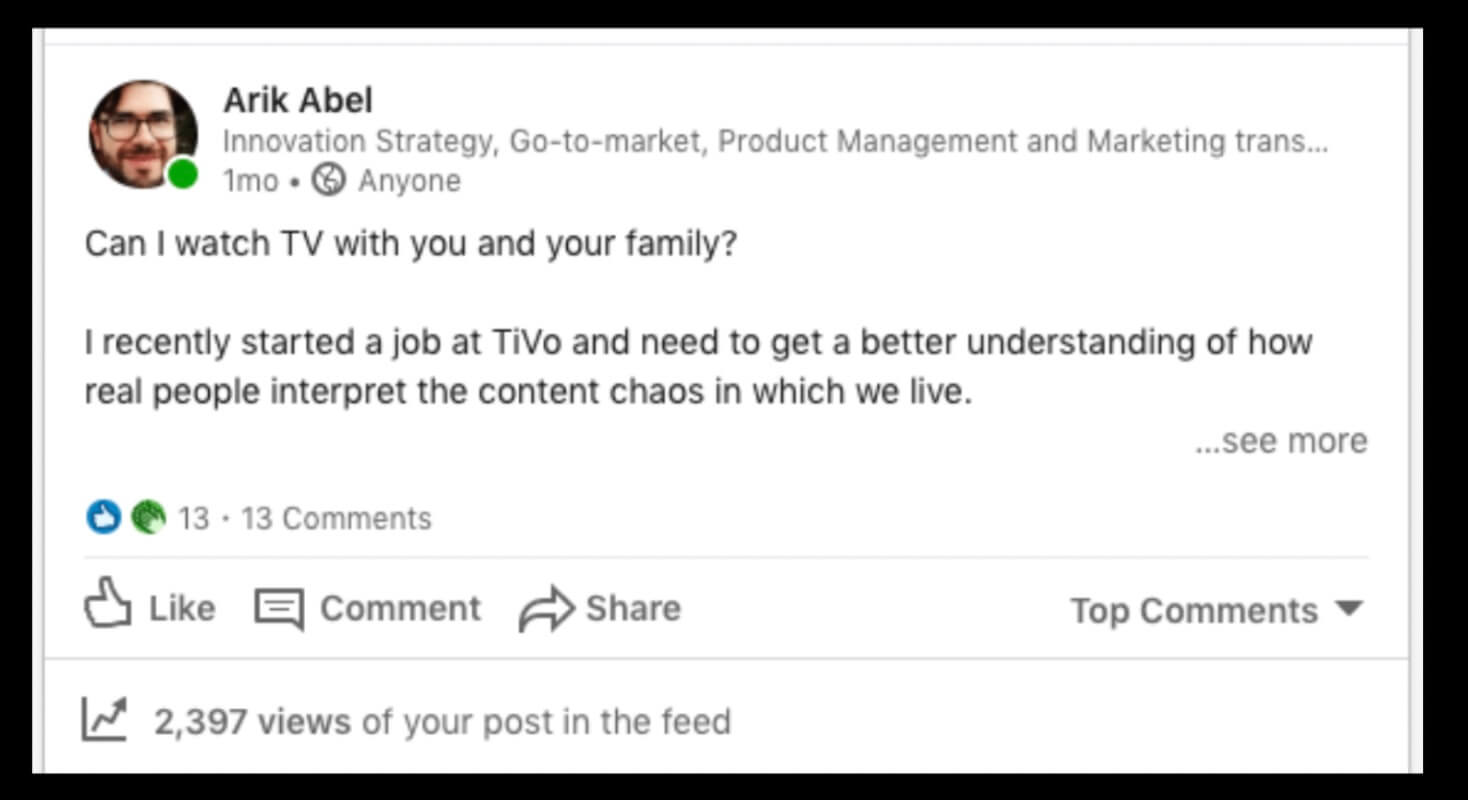

When I joined TiVo recently, it was a whole different industry for me and the first thing I did was reach out online and try to learn more about why people care about entertainment because I know we love binge-watching all of our favorite shows and all that stuff.

But I reached out to the community online and just said, 'Can I come to watch TV with you and your family?'

Because if you're in this idea of customer empathy and design thinking, it's about being there with the people. You can't read stats and have the kind of insights that come out of customer empathy.

This is the process I've been going through for the last couple of months because I think as a product marketer, to be the one that understands the customer the most is the most valuable thing that you can do for your teammates.

I was actually really surprised to get a lot of great responses from people that said, 'Yes, you can come over and watch TV with my family'.

Takeaways

Human-centered design = a practice, not a process. It's not a checklist that you follow, it's just things that you do.

You've got to frame the right problem and get others involved.

It's very visual and tactile, that's one of the things I love about it.

Thank you.

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn

.svg?v=7919bee89c)